Early in his reign, Edward VII ordered the redecoration of Buckingham Palace. The rooms in the north side were modernised with electricity and bathrooms for occupation by The King and Queen, and the state rooms were painted in red, white and gold, a choice considered a trifle vulgar by some courtiers, who likened the new colour scheme to that of a continental opera house.

The Edwardians: Age of Elegance at the King's Gallery

24th June 2025

This summer, Buckingham Palace explores the exquisite taste of the Edwardians at the King's Gallery. Lucinda Gosling reveals the stories amid the glitter and gold in this feature from The Illustrated Royalty in Britain.

Nevertheless, it was a facelift with the necessary punch and bling for a building which, after decades of disuse, was being restored to full glory as the official residence of British royalty. Paintings from Marlborough House were brought over to be hung at the Palace, and The King would spend time watching and directing the rearrangements both there and at Windsor Castle. “I do not know much about art,” he would say, according to Lionel Cust, Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, “but I know something about arrangement.”

‘The Edwardians – Age of Elegance’, this year’s exhibition at the King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, pays tribute to the taste of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, sharing almost 300 pieces of art, ornament, jewellery, books, sculpture and ceramics, about half of which have never been on public display before. For a monarch who in popular imagination is sometimes better known for his connoisseurship of women, racehorses and cigars above art and literature, here is a show that seeks to delve beneath that surface, sharing treasures that reflect the magnificence of the Edwardian court, and the artistic and cultural touchstones of the times.

The exhibition takes necessary liberties with the period it covers, suggesting that the ‘Edwardians’ became a phenomenon several decades before The King’s nine-year reign. Consequently, there are many objects that pre-date the official Edwardian era, while the exhibition also extends beyond it into the reign of George V and the outbreak of the First World War.

The majority of Edward VII’s life was spent as a king in waiting, during which time, he established his own court at Marlborough House. He surrounded himself with a cosmopolitan mix of friends and acquaintances; the witty and urbane Portuguese ambassador, the Marquess of Soveral; hunting and shooting members of the aristocracy; wealthy Jewish families like the Rothschilds; and men such as Ernest Cassel, whose financial acumen would prove indispensable to the future King.

The so-called ‘Marlborough House set’ could not have been more different to the fusty, conservatism of Queen Victoria’s court. She considered them ‘fast’; an opinion not without foundation – Bertie, as he was known to intimates, was embroiled in several embarrassing scandals linked to gambling disagreements and complicated love affairs among his acquaintances. Strained though the relationship was between Victoria and her son and heir (she refused to involve or educate him in any of her official duties as monarch), family, bloodlines and continuity meant much to The Queen, a fact reflected in one of the exhibition’s flagship paintings.

‘The Family of Queen Victoria in 1887’ by the Danish artist Laurits Tuxen, was commissioned by The Queen to mark her Golden Jubilee. Tuxen’s carefully configured scene shows Victoria (and Albert, in the form of a bust on the mantelpiece), surrounded by her children, their spouses, grandchildren and great-grandchildren in the Green Drawing Room at Windsor Castle, an epic work reflecting the expansive web of marriages that had seen The Queen’s progeny established across the courts of Europe.

For Tuxen, the arrangement of the scene was a diplomatic nightmare, with certain family members refusing to be placed alongside others, but the positioning of The Queen’s son and heir in the centre of the picture is significant, even if Bertie is perhaps outshone by his brother-in-law, the Crown Prince of Prussia, standing to one side in his gleaming white uniform (the tall and imposing Fritz would be dead of throat cancer within the year, having ruled as Emperor for just 99 days).

There are four more Tuxen paintings in the exhibition, all worth lingering over, including ‘Garden Party at Buckingham Palace, 28th June 1897’. It depicts the elderly Queen in her Diamond Jubilee year, accompanied by the Princess of Wales riding in an open carriage among the smartly dressed throng on the palace’s sun-dappled lawns. Bertie showed great interest in the progress of the picture and visited Tuxen at Windsor and Copenhagen to discuss the composition. He can be spotted on the left of the picture in conversation with an elderly couple; while scanning the canvas it’s also possible to pick out the future George V, politician Joseph Chamberlain and actor Henry Irving among the guests present that day.

Spectacular social occasions punctuated Bertie and Alix’s annual schedule, including several costume balls, evidence of which appear in the exhibition. The photographer Lafayette captured Bertie looking faintly preposterous as a knight of the Order of Malta at the splendid Devonshire House ball in July 1897 and a quarter of a century earlier, Godefroy Durand’s painting of a fancy dress ball held at Marlborough House on 22 July 1874 records for posterity the costumes which were designed by the artist, Sir Frederick Leighton, which included a wig of incongruous yellow curls sported by the Prince of Wales as Charles I.

A friend of Bertie, who often offered advice on art, Leighton was one of the 19th century’s most in-demand artists, and his work is on display here alongside other fashionable painters of the day, including Lawrence Alma-Tadema, John Singer Sargent and Philip de László, an artist who easily rivalled Tuxen when it came to the number of royal portraits churned out of his studio.

Family gatherings and jubilee celebrations aside, Bertie’s opinion was that his mother’s 40 years of reclusive widowhood had resulted in an unsatisfactory and lacklustre reign. On ascending the throne, he was determined to restore the traditional pomp of ceremonial functions, and inject some much-needed glamour into the monarchy. For the opening of his first Parliament on 14 February 1901, the cobwebs were blown off the State Coach and The King chose to wear the Imperial State Crown for the occasion (last worn in 1861). “I wished it to be in as grand State as possible,” Bertie wrote to his elder sister Vicky. Court presentations, previously held as afternoon drawing rooms, became glittering evening affairs.

The King had visited the courts of Prussia and Russia regularly during his long tenure as Prince of Wales, where appearance, spectacle and rank was everything. Add to this his extensive experience as an avid theatregoer and in short, Edward VII knew how to put on a show. He was admirably supported in this by his wife, Alexandra, who appears on canvas in another Tuxen picture, showing the moment of her anointing by the Archbishop of York at the 1902 Coronation. Although the official Coronation picture commission was given to Edwin Abbey, as a fellow countryman, Tuxen was made, ‘Queen Alexandra’s Special Artist to the Coronation’ and was given a prime position near the altar, hidden behind the tomb of a Norman knight, where he was able to observe proceedings close up.

Tuxen laboured over this and two other coronation scenes, working on them between 1902 and 1904, writing to his wife, “I consider myself on a treadmill, tramping over acres of gold, which is a shame to admit as it’s all so magnificent.” He found some of the subjects uncooperative when it came to granting further sittings and was eventually obliged to paint the Duchess of Marlborough from a photograph.

Alexandra’s increasing deafness made court life trying at times and she preferred to spend most her time at Sandringham in the company of her daughters and dogs. But when called upon, she could be counted on for a dazzling regal display. Hailed by Vogue as “the legitimate head of fashion throughout the British dominions”, she was impeccably dressed by some of the finest English and Parisian dressmakers, Redfern, Worth and Doeuillet among them. An exquisite 1908 portrait of The Queen by François Flameng, confirms her status as a style icon. Alexandra, in her sixties, appears elegant and dignified, framed by a swathe of frothy tulle, a Cartier choker around her swan-like neck and her famously trim, wasp waist still very much in evidence.

Visitors to the exhibition can also see The Queen’s Dagmar necklace, a wedding gift from her father, the King of Denmark, in 1863, while further scintillation is provided by Queen Mary’s Love Trophy collar necklace by court jewellers, Garrard, on display for the first time. Queen Mary may not have had the style cachet of her mother-in-law but nobody could quite carry off jewellery like her, draped with diamonds and pearls, the longer strands spilling over her impressive embonpoint.

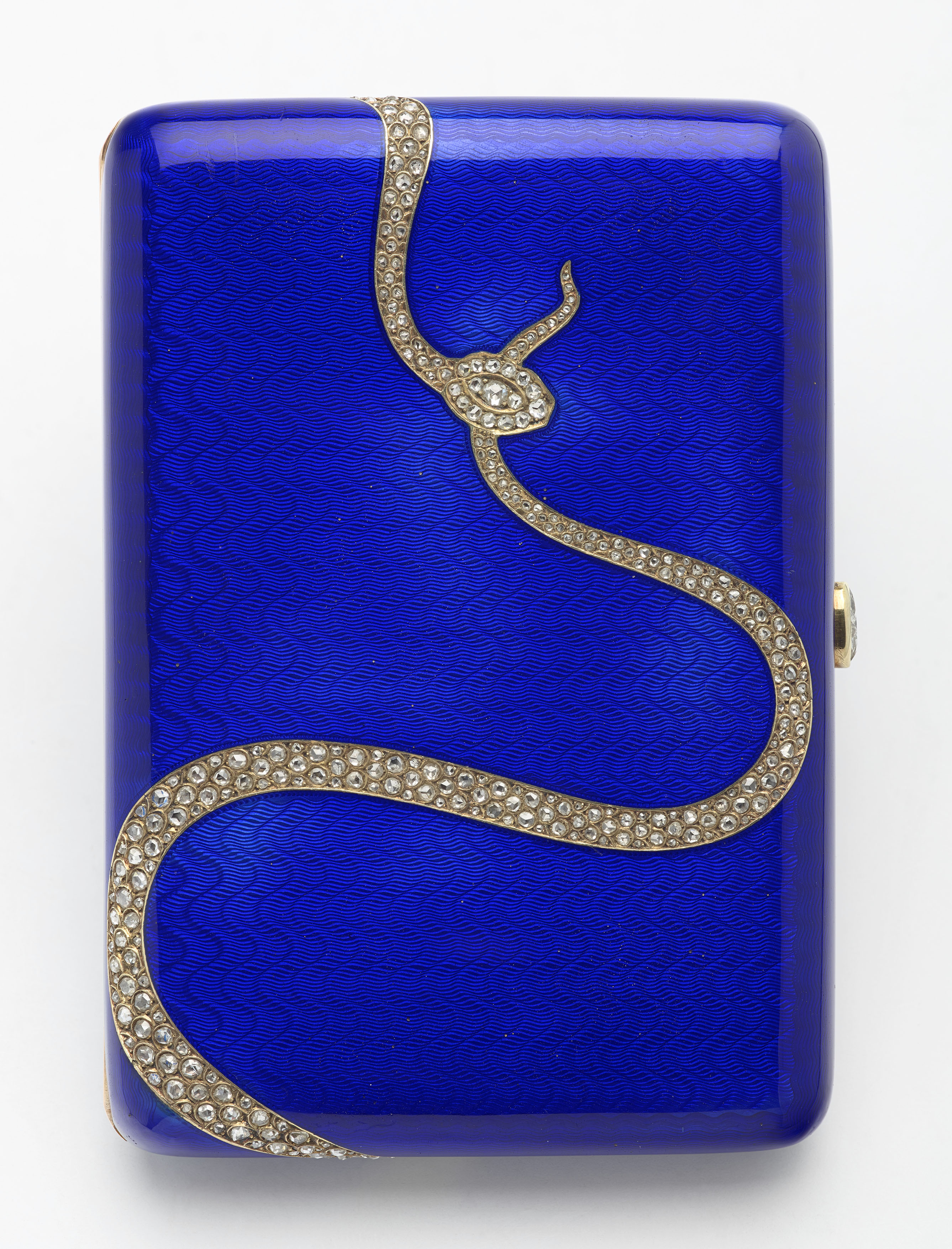

There are plenty more baubles and objets d’art to gasp over, including 20 pieces by the great Russian jeweller, Carl Fabergé. Bertie and Alix were introduced to the work of Fabergé by Alix’s sister Dagmar, the Russian Empress, sparking an enthusiasm which would see the royal collection grow over the years as the British, Danish and Russian royal families gifted each other various ornaments and bibelots. This taste for trinkets continued unabated; a photograph taken by Mary Steen of Queen Mary when Duchess of York, in York House, proves beyond doubt that maximalist, fussy interiors were de rigueur.

Displays in the exhibition are arranged to evoke the fashionably cluttered interiors of the royal residences at Marlborough House and Sandringham House, where decorative objects and family photographs covered every available surface. It is perhaps reductive to label these objects ‘trinkets’ when they include a Cartier crystal pencil case studded with diamonds and rubies, or a Fabergé cigarette case of blue enamel decorated with a gemstone-encrusted serpent.

The latter item holds special significance. It was a gift from Alice Keppel, The King’s last mistress, given to him in 1908 as a token of her devotion. Small and perfectly formed, it’s one of the few objects to hint at human frailties and passions among all the splendour on display, a true symbol perhaps of the Edwardian age of elegance.

Travel Tokens

Although Queen Victoria travelled to Italy and France during her reign, it was her son who established the tradition of royal tours, travelling extensively both before and during his reign. His tours helped forge diplomatic alliances and aimed to strengthen bonds between Britain and its colonies.

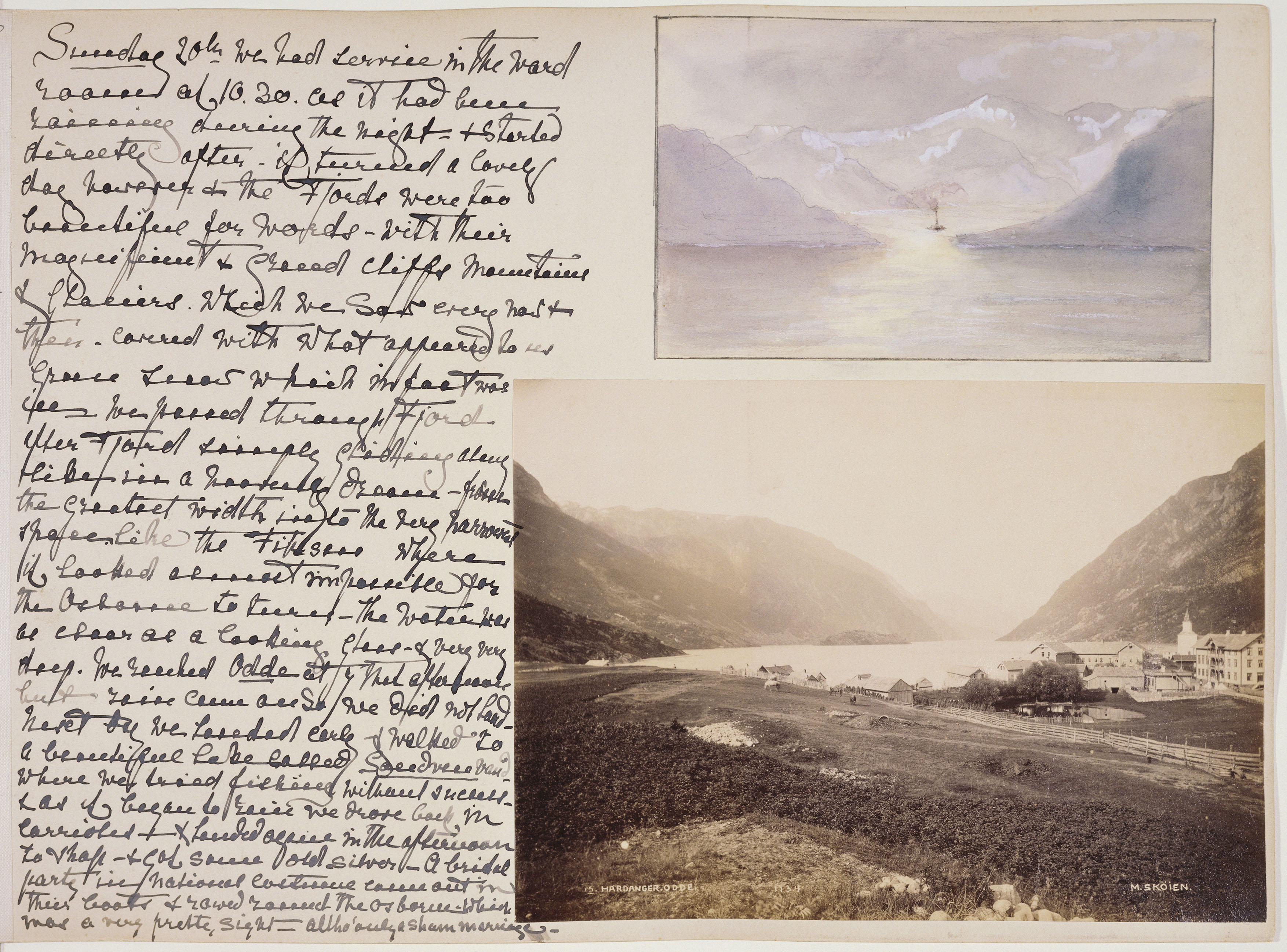

The exhibition features items from their travels on five continents, including an Egyptian scarab brooch given to Alexandra by Edward following his tour of the Middle East in 1863, and Alexandra’s handwritten notes, watercolours and snapshots from her visit to Norway in 1893.

Patrons of the Arts

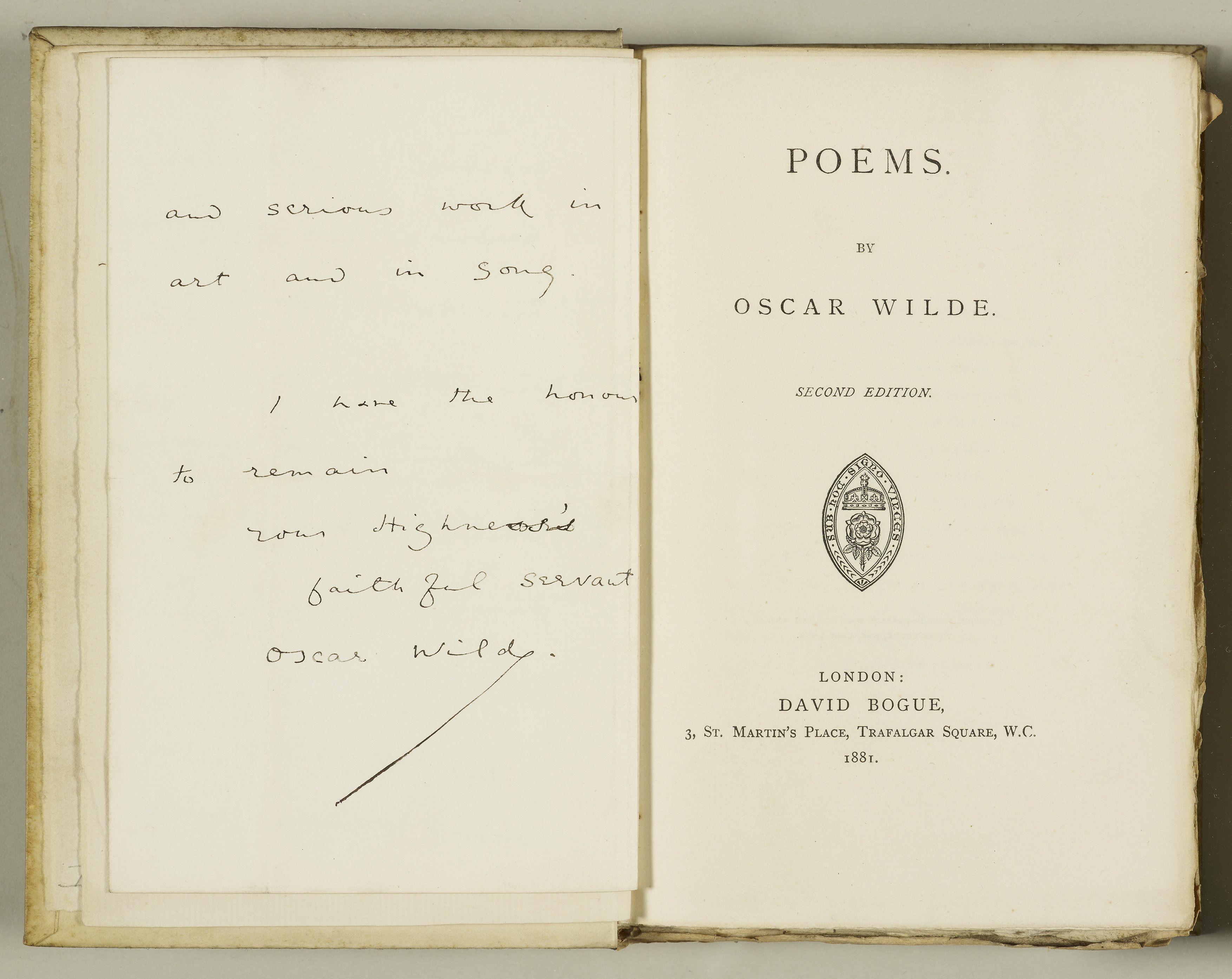

An interest in new artistic movements such as Aestheticism, Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts is reflected in the collection of Edward and Alexandra, which includes a copy of Oscar Wilde’s Poems, personally inscribed by the author, as well as an early edition of the first book printed by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press. In 1902, Edward founded the Order of Merit to recognise contributions to cultural and scientific life. Recipients included Sir Edward Elgar and the physicist Sir J J Thomson, and a portrait of each was drawn for The King, a tradition that continues to this day.

‘The Edwardians – Age of Elegance’ is at The King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, until 23 November 2025