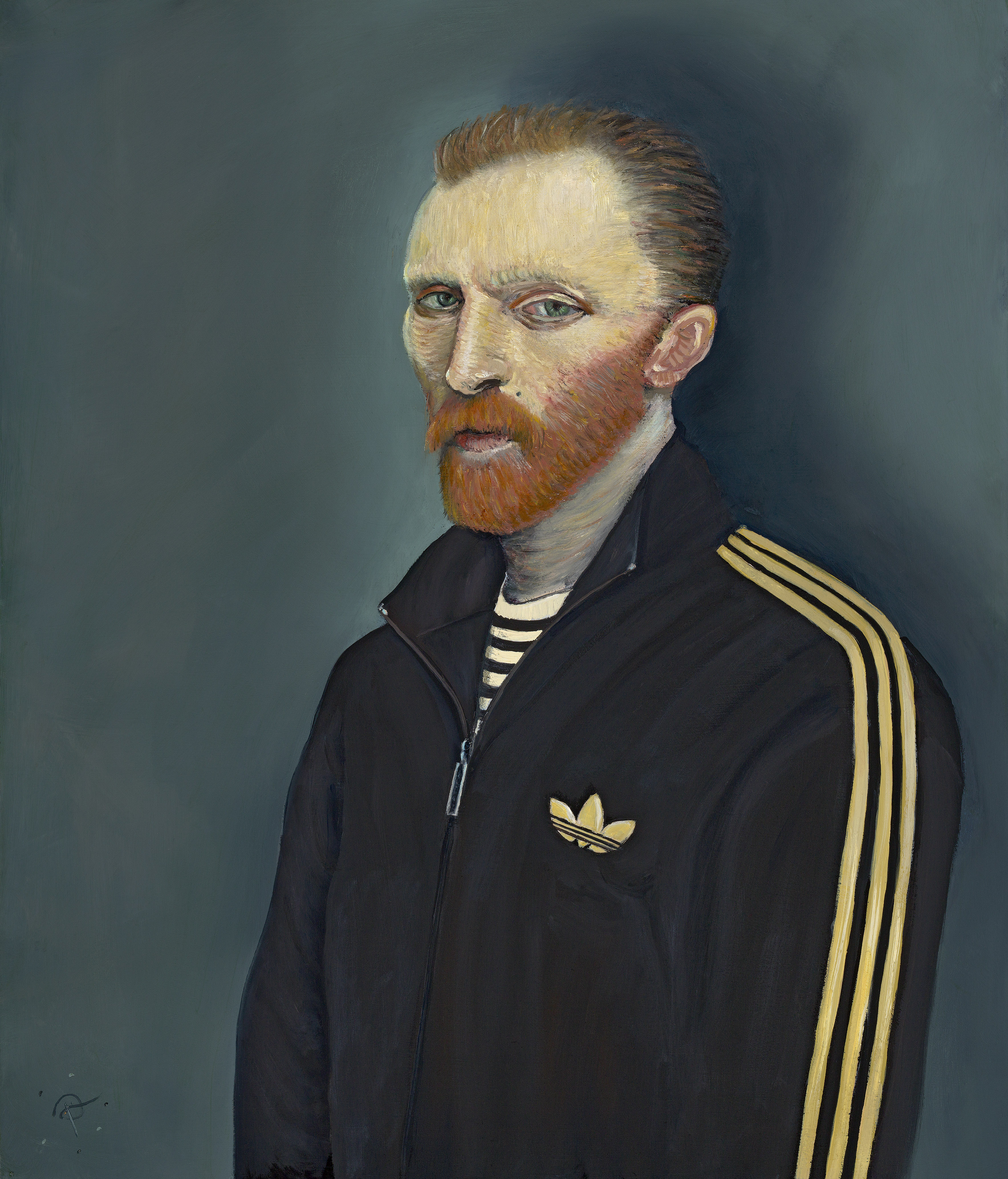

When Maddox was founded in 2015, creative director Jay Rutland found the art world “quite unwelcoming, quite elitist.” The intention for Maddox, he explains, is to be “the antithesis of that, to be a welcoming gallery, to be a fun gallery, and to not do things in conventional ways.” So whether you are a seasoned collector or somebody who’s never bought a piece of art before, “when you walk through our doors, you’ll be treated the same.” It’s the perfect approach to chime with the way rising talent and big-league artists as well as galleries established and niche, are embracing social media platforms. Social media not only helps them tell their stories but also lets them traverse geographical, cultural and political boundaries in search of new, enthusiastic audiences keen to invest in a $1.7 trillion global marketplace where sales of contemporary art have increased by 600% in the past two decades. So how has social media changed the art industry for the better? GOING VIRAL In late 2020, Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum posted Ross Muir’s Jist Gogh Hame version of his Square Gogh artwork on its Instagram feed. Square Gogh is the Scottish artist’s reimagination of Vincent van Gogh’s iconic self-portrait, which he’d turned into posters to plaster around Glasgow during the pandemic. The image garnered over 30,000 likes, and Muir’s standing in the art world skyrocketed. It also inspired Maddox (@maddoxgallery, 150,000 followers) to stage Muir’s first major exhibition in the UK earlier this year, an instant sell-out.

Follow Your Art: Can Social Media break an artist?

27th September 2022

Social media lets artists and galleries tell stories and traverse boundaries — particularly among younger collectors

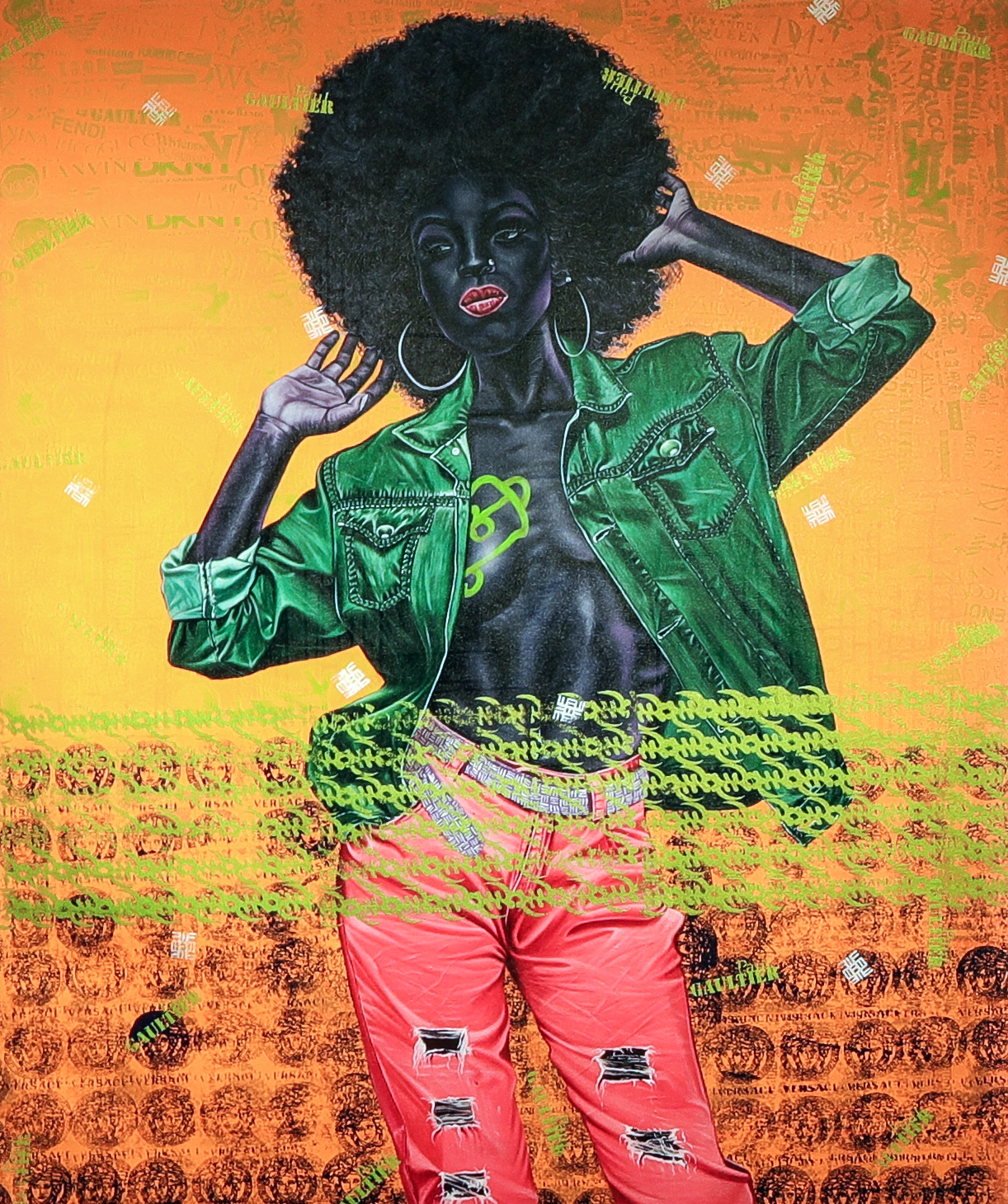

Maddox’s recent What Lies Within Us exhibition, held in its Notting Hill outpost, was powered by artists such as Daniel Onguene and Jack Kabangu, found by searching on Instagram. The exhibition was curated as a platform for artists to create works which reflect their own personal and cultural identities, freed from traditional confines of gender, race, sexuality or geography, thus encouraging inclusivity. It gave voices to a new generation of artists. “I always knew I wanted to be an artist, but not how to be an artist,” says Dawn Okoro, who participated in the show.

Many artists use social media to reveal the intimacies of their creative process. It’s the ideal way for a potential or existing collector to develop a dialogue with either an artist or a gallery, laying the foundations for long-term patronage. From Damien Hirst (@damienhirst, 926,000 followers) writing about the origins of his first Spot paintings or Takashi Murakami (@takashipom, 2.5 million followers) sharing videos of himself at work in his studio to rising stars such as Cooper (@iamcooper, 34,300 followers, featured in this issue), who photograph themselves with their work to give an idea of scale and perspective, social media lends further meaning to artists’ work.

According to the Art+Tech Report 2021, for collectors aged 20 to 40, social media is almost as important as gallery or artist websites for staying informed or getting to know an artist they may not have previously been familiar with. New York-based Jerkface (@ incarceratedjerkfaces, 218,000 followers) and Banksy (@banksy, 11.1 million followers) are among the “popular artists who have proved they can increase their fame and engagement with collectors via social media while maintaining their anonymity,” says Maddox’s artistic director Maeve Doyle. The magic of social media is particularly significant when it comes to reaching a younger demographic: over the pandemic, almost three-quarters of online art buyers bought more than one artwork online, reported international specialist insurer Hiscox in 2021. According to Artsy’s Art Collecting 2021 report, next-generation collectors (those who started collecting in the past four years) prefer to discover new artists while scrolling on their phones.

Some argue that once you’ve seen something on Instagram, you no longer need to see it yourself, but when it comes to art, the opposite is true. There is a certain kudos that comes from being there. Take the 90,000 or so hashtags accompanying the selfies shot within the thousands of little dots reflected off the mirrored walls and watery floors of one of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms, for example. The upside is that more people are exposed to new artists and ideas, while creating a space where the observer also becomes part of the show. The success of graffiti artists like Brian Donnelly, aka Kaws (@kaws, 4.2 million followers) and Stik (@stik, 64,800 followers) has been driven by the passion of their Instagram fans rather than relying on the endorsement of the traditional art world. Donnelly’s painted artworks now sell at auction for millions.

“Our openings are very different from a usual gallery opening — often there’ll be a performative element,” Rutland says of the fantastic façades decorating Maddox’s Mayfair flagship gallery. These include last year’s giant iced doughnut, accompanying Jerkface’s first UK solo exhibition Villainy, sold out before it opened. The Connor Brothers’ A Load of Fuss About Fuck All show (@connorbrothersofficial, 42,800 followers), featured a giant-sized Marilyn Monroe, her skirt a cascade of yellow blooms flowing around the gallery’s windows and down to street level. “We do things in a different way because it’s more engaging,” says Rutland. Naturally, selfies are encouraged (and social media is relied upon to pique the curiosity of existing and potential new collectors alike) — also, a space where anything goes encourages artists to approach the gallery with their work, bypassing the old mores of requiring old-school connections to get their portfolios through the door. At Maddox, the door is wide open and welcoming.

Follower numbers correct as of August 2022; maddoxgallery.com