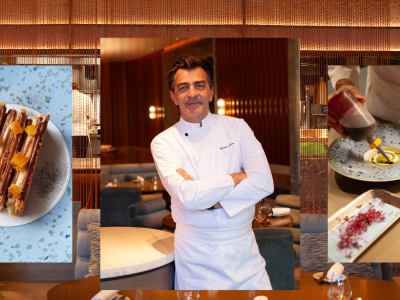

I am sitting with Chef Yannick Alléno at Pavyllon London at Four Seasons Park Lane and ask him where in the world he would dream of opening a restaurant. “The moon,” he replies, without missing a beat. As one of the most decorated chefs in the world, this may not be mission impossible. Alléno’s constellation sparkles — 17 Michelin Stars across 19 restaurants, second only to Alain Ducasse. In March 2025, his restaurant L’Abysse Monte-Carlo at the Hôtel Hermitage Monte-Carlo was awarded two Michelin Stars after just eight months of opening, and last year Pavyllon London earned one Star after six months.

Inside Pavyllon: A Conversation with Chef Yannick Alléno

13th July 2025

Super chef Yannick Alléno, known as the reinventor of French cuisine, was recently awarded his 17th Michelin Star. In an exclusive interview with SPHERE, he reveals the secret ingredients of his success, from Pavyllon London to L’Abysse in Monte-Carlo

There are currently three Pavyllon restaurants in the world, with London being the most recent, and it’s set to expand. Pavyllon Dubai opens in the autumn at the new Mandarin-Oriental Downtown Dubai, and Pavyllon Lyon École, the first training restaurant in Yannick Alléno Group, will open later in the year. The concept for Pavyllon is about everyday dining. “The brand came from Pavillon Le Doyen in Paris,” explains Alléno. “The ‘y’ in the middle is for fun [Yannick]. That restaurant created the link from three Stars to the city. Three Stars are for special occasions, and Pavyllon is for all-day use. You can come for breakfast, a business lunch, or something light in the evening. You know you will have a wide choice of dishes, great service at the counter, and a nice wine list. It’s open seven days a week, so you don’t need to check your phone to see if it’s open.”

Dining at the counter is central to the Pavyllon concept, inspired by Alléno’s childhood, when his parents ran bistrots on the outskirts of Paris. Each Pavyllon (London, Paris and Monte-Carlo) has a sweeping counter. Alléno enthuses: “The ‘comptoir’ is fantastic for the proximity with guests. It’s the theatre of food. At a table, you’re in your own intimate space. The counter makes it easy to talk with guests.” In person, this 56-year-old Frenchman is refreshingly candid, down-to-earth and funny. I ask Alléno how he has celebrated getting new Michelin Stars.

One occasion is etched on his memory. He confesses that when Le 1947 at Cheval Blanc, Courchevel was awarded three Michelin Stars in 2017, he celebrated over lunch with his wife and a friend from Caves Legrand. “We started to drink too much of very good wines. Then I saw my phone ringing. Bernard Arnault! ‘If you have time this afternoon, I would like to congratulate you.’ I suggested the next day would be better, but he was taking a plane.” So Alléno got a driver and devoured two packets of Fisherman’s mints. “I tried to stand up. He hugged me and thanked me for my passion. We had waited eight years for this. He said, ‘It’s the beginning of what we do.’” Alléno is still standing and Le 1947 retains its three Michelin Stars.

Breakfast and brunch are another highlight of Pavyllon. Sunday Brunch by Alléno, at Pavyllon Monte-Carlo, with a feast of superb pastries and inventive light dishes, was indisputably the best brunch I have had in my life. Breakfast at Pavyllon London is already a thing. Its Avocado Croast has had 30 million views on Instagram to date. While Pavyllon has a recognisable formula, the focus is firmly on seasonal and local: “We purchase the ingredients close to the restaurants,” Alléno says. “The fish in Monaco comes from the sea in front of us, and we have our own fish sellers. We don’t transport food from France to London. We work with suppliers: beef, lamb, vegetables, even butter and cream. You don’t have the same needs in London as you do in Monaco, where it’s 40 degrees.”

Alléno admits that London is not an easy market: “London doesn’t wait for me. There are so many great restaurants, so much energy. I look around and it’s very diverse, and very cosmopolitan. There is nowhere else like it. So Pavyllon London has to take care of these things. I want Pavyllon to be accessible and cool, and the prices are super-okay, if you look at the competition.” Opening new restaurants is a risky business, and Alléno has a canny and proven model. He is a strong believer in partnerships between hotels and restaurants, so it’s a win-win. He doesn’t limit the collaboration to one group and Yannick Alléno Group works with Four Seasons, Monte-Carlo SBM, One&Only, Cheval Blanc (LVMH), and soon Mandarin Oriental. He describes the advantages of working with Four Seasons Park Lane: “It’s so much easier with a hotel, because around the restaurant you have a whole infrastructure and a crazy energy — sales, marketing, PR, HR. You go faster and you go higher. So when you have that kind of investment, it’s a big partnership. To support it independently would be impossible. For my brand to be linked with Four Seasons is fantastic.” The Hôtel Hermitage in Monte Carlo is another example: “It has an amazing terrace, views of the castle and the port, and a car valet. If a customer spills tomato sauce on his shirt, the hotel can change it. The facilities and advantages are extraordinary.”

But with a portfolio of 19 restaurants in the group, how can the Chef Honcho continue to retain high standards and remain in control? After all, Gordon Ramsay has held a total of 17 Michelin Stars and today has seven. Chef Alléno, does this worry you? Alléno’s response is that he oversees the creative aspects and is keen to nurture new talent (he has an official role as a mentor to up-and-coming Michelin-Starred chefs). He has a strong band of Executive Chefs, such as the dynamic Chef Benjamin Ferra y Castel at Pavyllon London, with whom he has worked for 10 years. Alléno explains: “I’m the Artistic Director. We have to put the new generation on the stage. When I hire new chefs, I ask them, ‘Why are you here? If you don’t work for yourself, we have a problem. You need to look at your own destiny.’ We give them the keys for their own success. My method is about freedom: freedom to propose, create, talk, share and take some risks. It’s a matter of organisation, methodology, precision and trust.

And we communicate — I probably receive about 100 WhatsApp messages a day. It’s like they are my kids. “When the chefs have a picture of a plate, I know what they need to change. Last week, a young pastry sous-chef sent me a picture of a dessert. I said, no, you need to go in this direction. Two days later, he sent me back a new picture and I said, ‘I think he’s right.’ He was very proud. The dessert was perfect. We rank every dish. What he first proposed to me was about 20 points, and today I’m pushing him for 70 points.” Alléno is often described as “the reinventor of French cuisine”. Why? It’s all about the sauce, which he describes as “the verb” of cooking. He has been obsessed with sauce-making his entire life, and his hero is Auguste Escoffier. Alléno’s signature technique is extraction, and he intensifies flavours using a method known as cryo-concentration, which defies convention as it involves freezing and thawing ingredients. Precise cooking temperature and timing protect all of the ingredients from heat, concentrating natural flavours and creating a unique texture.

Besides Escoffier, what have been the driving influences in Alléno’s culinary career? It started with his family upbringing. Summers were spent with his beloved grandmother, who had 13 children — his mother was the 12th child — and an army of cousins. Three or four cousins would share a bed, top and tail. His mother, Isabelle, has more than a hundred nephews and nieces. His cousin Jean-Marc, 10 years older, was his “tuteur” and took the young Yannick under his wing. At 17, Jean-Marc worked in the kitchens and would take his charge with him. “I understood then I was happier with adults.” It was at his grandmother’s house that the young Yannick understood the importance of ingredients. The summers were about preserving food for winter, such as chicken in a bottle. His grandmother taught him that the quality of water was vital for cooking, and she always took water fresh from the well.

He also pays tribute to Alain Passard: “What he did is fundamentally important, especially with vegetables. In 2000, with three Michelin Stars, he stopped feeding people animal protein. He said, ‘I don’t want to poison my guests or myself. Maybe Michelin kill me.’” Luckily, the Michelin inspectors saw the bigger picture and L’Arpège has kept its three Stars since 1996, moving from rotîsserie to vegetarian. Finally, Japan. “I went in ’88 and fell in love with the country. Their food is culture. L’Abysse is a mix between two cultures. I know perfectly what sushi is. I spent one week with Mizutani san [the sushi Master in Tokyo] at his personal place. He taught me the importance of rice, temperature, the time cooking fish, the importance of the rice. Sushi is a piece of art.”

Where does Alléno like to dine out in London? Poppy in Soho for fish and chips. Josephine in Marylebone, Claude Bosi at Bibendum, Core by Clare Smyth for three Stars, Taku for sushi and Scott’s for oysters. If he has any spare time, he enjoys visiting art galleries and enjoys kick-boxing. He has a keen eye for design — he pauses our interview at one point because the seam of the lamp shade is visibly facing the table. Wine is a passion, and he has a partnership with Michel Chapoutier, producing wines in the Rhône called Y/M. Asked what kitchen item he would take to a desert island, he first quips, “Who with?” Then he asks if he can have two items. The first is a bottle of Château Haut-Brion, and the second, a corkscrew. What’s next for Alléno? His first pop-up at Royal Ascot is in the pipeline. But my money is on “Alléno and Elon” launching in space. You read it here first in SPHERE.