Marilyn Monroe may have sexily crooned “diamonds are a girl’s best friend” in 1953, but over 70 years on, we are living in more equal times. For the last decade and more, diamonds have become the best buddy of many wealthy men. Not often for wearing themselves, though there is indeed some of that, and not always for the time-honoured reason of bestowing a gift on a loved one.

Classic Diamond Jewellery to Invest in

19th January 2026

Classic diamond jewellery is shining bright once again ahead of Valentine's Day, with a dazzling array of options for both investors and jewellery fans alike.

Less romantically, a large diamond is today an essential part of the ultra-high-net-worth individual’s investment portfolio, the ultimate expression of portable wealth. As Coco Chanel explained why she only worked with diamonds for her one-off 1932 high jewellery collection, the gems have “the greatest value in the smallest volume.” Nothing has changed in nearly a century. At this level, the diamond’s relation to actual jewellery is practically accidental; it’s often secreted away in a bank vault where the owner hopes it will gather value in the dark. In short, large, top-quality diamonds are now a luxury commodity alongside art, classic cars and Hermès handbags.

The top diamond price so far is $71.2m (including fees) for the CTF Pink Star, a 59.60 ct oval, fancy vivid pink, internally flawless stone sold by Sotheby’s Hong Kong in 2017. A rich pink stone this big is almost unheard of, and pink diamonds have extra cachet for their rarity, especially since their main source, Australia’s Argyle Mine, closed in 2020, though the Star was mined in Africa. The most expensive white diamond yet is a 163.41 ct pear-shaped stone sold by Christie’s in Geneva the same year for $33.7m. That those peaks were reached eight years ago does not necessarily indicate a slowdown — despite fluctuations, average prices for diamonds of 2 to 2.5 ct have risen nearly 10 per cent in the past three years, and larger stones rise much faster due to their rarity.

All of which sounds welcome news for the investor, less so for the jewellery fan. However, there are two sides to this story. Prices for smaller diamonds are dropping significantly. According to diamond market analysts Tenoris, prices for 1 carat diamonds decreased by 26 per cent in America — the world’s biggest jewellery market — between May 2022 and the end of last year. There are several reasons: economic and political uncertainty, the falling popularity of marriage, a slowdown in China, and younger generations preferring experiences to possessions. The biggest reason is the advent of lab-grown diamonds, identical in chemical and physical detail to natural diamonds and forecast by Morgan Stanley to make up over 21 per cent of the market this year, driven largely by younger consumers’ environmental and ethical concerns. Increasing production and cheaper methods have forced their price down by over 70 per cent in five years, but investing is not their customers’ chief concern.

Meanwhile, the price of gold — always a safe haven in troubled times — reached a record price of over $3,200 per ounce in late October, and many jewellers say their biggest cost is now gold, not diamonds. The final price for a piece of jewellery may not be dropping much, but consumers will enjoy the prospect of more bling for their bucks, especially applicable to pavé, made from mixes of tiny diamonds known as melée.

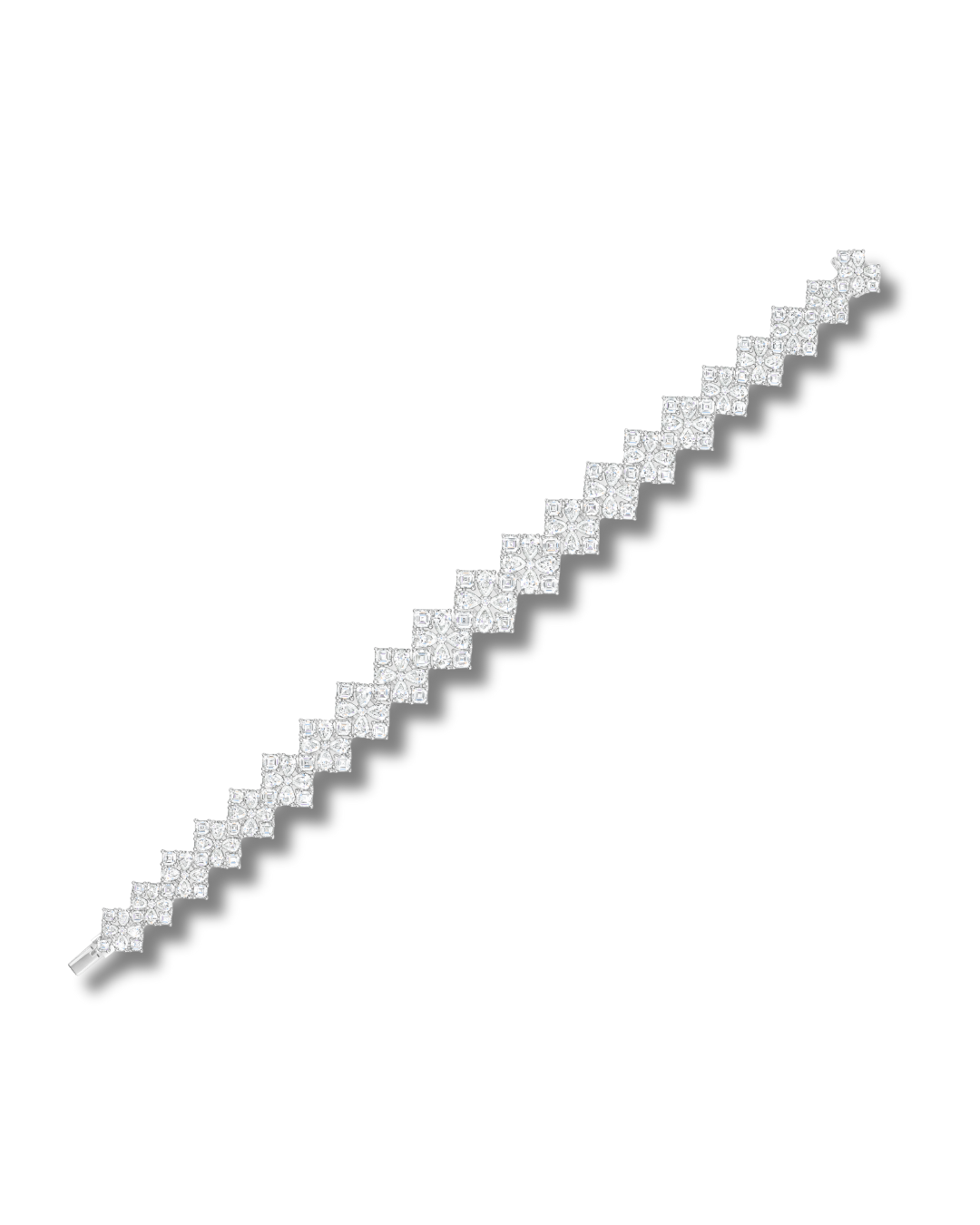

Perhaps it’s a coincidence, but while coloured gemstones, including diamonds (which represent a tiny 0.1 per cent of gem diamond production), feature in every high jewellery collection, the pure sparkle of white diamonds is resurging. Their wattage draws the eye more than the most wonderfully tonal coloured design. This was brilliantly exploited by Harry Winston, New York’s “King of Diamonds”, who invented the cluster setting — mixing different cuts in layers to refract maximum sparkle from every angle — and helped start product placement with Hollywood stars. In the firm’s high jewellery, nearly every diamond is of investment size, and even in their top-end fine jewellery, such as the Couture suite, the cluster setting ensures maximum brilliance.

In the UK, Graff arguably has access to the grandest diamonds through links with mining companies and acquisitions from mines in Botswana and Lesotho, noted for producing very large, fine-quality roughs. It owns the Lesedi La Rona, a 302.37 ct square emerald-cut, flawless quality stone cut from what is currently the fifth-largest rough ever found. Graff is also (relatively) democratic, turning out easy-to-wear motifs — chains, bows, butterflies — blazing with top-quality pavé, alongside its unique masterpieces. It helps if your family are diamantaires, like that of Paris-based designer Valérie Messika, who is celebrating 20 years of a business aimed at women buying their own diamond jewellery. Her ideas include double-finger rings and her trademark Move motifs, executed in perfect pavé, often with a punk-inspired edge.

Another way for brands to obtain great diamonds is to be a sightholder — selected by main trading company De Beers for a regular allocation of mixed-quality roughs, which the brand processes. This has less prestige in depressed times, but as the only sightholder in Japan for 30 years, Tasaki, primarily an innovative pearl brand but with a wider remit especially in high jewellery, creates beautiful, classic pieces featuring serious stones surrounded by mixed cuts.

Sourcing stones is never an issue for great, historic jewellery houses, and diamonds of all shapes and sizes are their stock in trade, as Cartier’s recent V&A exhibition emphasised. Its archives encompass virtually all the jewellery-making materials known, generally further enhanced by diamonds. Yet, in the phantasmagoria of every high jewellery collection, there are a few outstanding white-only pieces. For example, Cartier’s current style revolves around a complex geometry of stones, woven into whichever of its signature styles the designers deem appropriate — ranging from Art Deco or the romantic guirlande style to a tougher, more modern abstraction. The latest collection, En Équilibre, displays them all.

Boucheron is also historic, yet under its highly innovative creative director, Claire Choisne, it produces extraordinary work at the boundaries of jewelcraft and advanced technology. Alongside, its Histoire de Style high jewellery focuses on white diamonds, and some very classy fine jewellery spins off. The latest, Flèche, is inspired by an Art Deco arrow motif, now wittily twisted into elegant rings, bracelet and hoop earrings, as well as more conventional, but no less striking, straight pins and necklaces, all composed of faultlessly set small diamonds.

Couture houses now marketing high and fine jewellery are understandably influenced by fashion, which means a wealth of coloured stones. However, Chanel keeps white diamonds at its heart in homage to that 1932 original, strongly referenced by the latest collection, Reach for the Stars, based on Mademoiselle’s favourite symbols, including comets, wings and lions. Dior’s jewellery designer, Victoire de Castellane, adores colour and brings it very subtly into white diamond high jewellery, as tiny seed pearls or a white opal with very pale fire, while fine jewellery features all-white rose and thorn motifs.

White diamonds are also great for more minimalist design, from Pomellato’s Sabbia, with abstract “bud” discs snow-set — a tricky pavé technique with varied diamond sizes — on baguette stems, to Bucherer’s Rock Diamonds mixing small diamonds and polished white gold in shard-like trapezoid settings. Like every piece featured so far, the purity of diamonds is enhanced by setting in white metal — gold or platinum. But today’s jewellers are increasingly contrasting their diamonds with coloured gold, harkening back to early 1970s style and making it modern. Repossi’s new Blast pieces, featuring tribal- looking, ribbed rose gold scattered with pear-shaped diamonds at random angles, or Brazilian designer Fernando Jorge’s Vertex, set with baguettes in designs abstracted from vertebrae, are high jewellery options. Mouawad’s rose gold-set, diamond and mother-of-pearl butterflies, or Annoushka’s Knuckle ring, threading diamond pavé through a triple yellow gold ring, derived from a high jewellery design, are repeatable.

Similarly, designs like Smiling Rocks’ yellow gold abstract ring with a marquise diamond and their pavé and gold bean necklace, or Matilde’s sinuous rose and white gold Jupiter ring and Moon Drop earrings, exemplify this trend. These are two of the leading brands using only lab-grown diamonds and, in Matilde’s case, recycled gold. She shortly celebrates five years in business and notes “a fast-growing acceptance of sustainable alternatives, a real change in mindset towards a responsible luxury future.” Diamonds may be forever, but deciding which and how we choose now includes some radical choices.

Our articles may contain affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a commission at no extra cost to you.