Try telling a watchmaker that the delicate cogs and wheels of the mechanism are not what best demonstrates his skills and he might drop his loupe in shock. But there is another side to the watch business, one which uses the dial, case, even the moving parts as canvases for precise, delicate works of art, using lacquering, cloisonné and filigree work. These are just some of the traditional skills, known as métiers d’art.

Time-honoured Traditions

14th October 2015

The skills required by traditional métiers d’artwatches are still in demand, but companies are also working with new and innovative techniques, as Josh Sims discovers

“The métiers d’art in watchmaking are just like those in works of art,” explains Edouard Mignon, head of product development for Cartier. “That they are all done by hand adds to the artistic status and makes each work unique.”

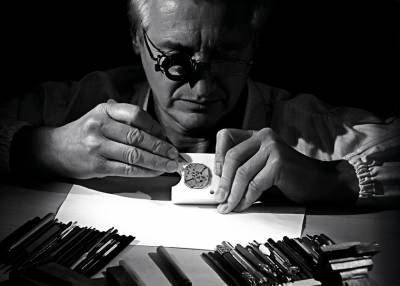

These skills are much in demand. Cartier’s new Maison de Métiers d’Arts, in Switzerland, houses 28 dedicated craftsmen whose work can only be properly appreciated with the use of magnification. For example, filigree, a skill in which the Maison has great expertise, entails twisting tiny gold and platinum wires, flattening them with a suitably small hammer, then soldering them — with an even smaller soldering iron — to create relief work.

“These artists require a lot of dexterity,” says Mignon. “And sometimes they have to adapt the technique because what looks and feels good on a one-square-metre piece of art perhaps won’t look so good on one square centimetre. When we did our first Roman mosaic dials, we had to completely re-think the technique because at the size of a dial, the stones don’t render as they would on a big mosaic.”

With such unusual, intricate finishes, métiers d’art watches are not only collectors’ items, they are important in terms of rescuing old skills, and also as a way of developing new ones. After years of work, Cartier has revived granulation, an art form that peaked around 800BC with the Etruscans. It involves the “sowing” of gold granules by flaming them in charcoal dust and individually fusing them on a gold plate to create a relief. The panther head on its Rotonde de Cartier Panthère watch required 3,800 of these tiny beads, put together over 320 hours.

Last year, the company unveiled a new form of dial decoration on its Ballon Bleu De Cartier Floral-Marquetry Parrot watch. Real rose petals were dyed, preserved and fixed to tiny slivers of wood, which were hand-carved into shapes that mimic a parrot’s feathers.

“Métiers d’art are often associated with old crafts,” says Mignon. “Techniques might be known only through museum pieces and the technique itself might actually long be lost. You can work with museums, analyse the objects and re-invent the techniques. But we really feel that we can still innovate in this field, too, and develop a technique that never existed before.

“It is important to allow all the traditional trades to be kept alive through training new artisans, but also to think about the future of the trades, technically and creatively speaking.”

Jaquet Droz introduced three watches last year to show its skills in paillonné enamelling. The company helped develop the technique in the 18th century, using the grand feu enamel process, which involves coating tiny motifs cut from gold or silver leaf with a translucent enamel fondant and fixing them to an enamel base. The result has a distinctive luminosity.

Similarly, three years ago Hermès approached Agnès Paul-Depasse, a world-class artisan in the ancient craft of straw marquetry. They asked Paul-Depasse to use her skills to make

a dial that is particularly unusual because this organic material will change over time.

It was a tall order, requiring pieces of straw little more than a millimetre wide, which tend to twist and flex. Paul-Depasse developed a technique using slightly more amenable rye straw, which was coloured, flattened, cut, fixed to graph paper and worked to create patterned dials — one chevrons, one squares — taken from Hermès tie patterns. The resulting Arceau Marqueterie de Paille watches arguably helped put Hermès back on the watchmaking map.

“It was just a challenge to us to see if it could be done. And it can,” says Philippe Delhotal, creative director of La Montre Hermès. “In fact, we were really enthusiastic about the marquetry idea precisely because it had never been done by the watch industry before.

“The challenge is to treat the métiers d’art in a more modern way — to think about new materials, techniques and technologies to take them forward, to be more experimental.”

This year, the company combined French porcelain with Japanese art for the first time with its Slim d’Hermès Koma Kurabe. The dial was painted by Buzan Fukushima using the 19th-century Aka-e technique of painting in red on porcelain. The porcelain was then coated with a fine layer of gold before firing.

The métiers d’art of tomorrow may be very different in application and mood. Roger Dubuis, one of the younger haute horlogerie companies, took a more irreverent approach this year with its Excalibur Knights of the Round Table watch. His original Table Ronde watch had an enamelled dial and 12 rose gold knights, each cast and then hand-finished under a microscope, as they are only 6.5mm tall. The update has the legendary knights cast in bronze, set round a carved black jade table.

“There’s a sense of humour to it, for sure,” says Roger Dubuis’ managing director, Jean-Marc Pontroue. “When I first saw it, I thought the design was baroque and wasn’t sure we’d find an audience, but it has sold out and to people who have never bought a Roger Dubuis before. That’s because it has a point of view, a depth, and that’s the issue with métiers d’artnow. There’s an acceptance that it’s beautiful, but it has to go beyond that, to be creative, too, because at the high end of the watch industry there’s a customer who desperately wants something different, in style, movement and in these crafts. We’re only going to see more of them. After all, there’s a whole world of ancestral artistic know-how — in Africa, China, Japan — that is largely untapped.”

Another company seeking innovative ways to decorate is Romain Jerome, which is taking a fresh approach by using rare and unusual materials. Its watches have been decorated with moon dust, volcanic ash, metal and coal from the wreck of the Titanic. Its Berlin DNA watch, produced to mark the 25th anniversary of the city’s reunification, has a dial created using fragments of the Berlin Wall micro-moulded to a point of such purity that it becomes transparent. This allows its bird’s-eye view of Berlin to glow when lit from behind, evoking the night-time moment when the wall fell.

“We use the same craftspeople as those companies that use the métiers d’art term, but I do think that has been rather over-exploited,” says CEO Manuel Emch. “It’s great to defend that patrimony — that’s what the watch industry at this level is all about. But like contemporary art compared with classical art, métiers d’art needs to have a more joyful, more provocative aspect. And that’s coming.”