All explosions are not equal — not in the wine world, at least. Nobody loves a fruit bomb, those cheap and undistinguished wines that seem to use berries as bullets. But a natural detonation is very different, and a volcanic eruption, while often hugely damaging, can have surprising benefits. Vesuvius burying the city of Pompeii in lava in AD70 was a terrible tragedy, but we who can wander Roman streets preserved by ash for 2,000 years can appreciate the upsides. The same is true for wine.

Volcanic Wines Born from Europe’s Fiery Landscapes

12th June 2025

In volcanic regions, grape varieties grown in mineral-rich soil can produce volcanic wines with an eruption of memorable notes on the tongue. Nina Caplan takes a tour of some of Europe’s most unlikely vineyards, where fine wines are born from natural disaster.

Vineyards buried under boiling lava are a disaster: before AD70, the Vesuvius slopes grew the Roman Empire’s finest vines. But wait a couple of centuries. Volcanic soil is extremely fertile and full of minerals beneficial to vine roots. The best wines have an energy, like a seismic tremor, and they taste amazing: saline, flinty, and exciting, like licking a delicious rock. This is why there are so many volcanic vineyards, despite the risks. Modern predictive technology helps, but volcanoes are still scary. The last time Mount Etna, one of Europe’s most active volcanoes, erupted, in 2021, it emitted so much volcanic matter that the mountain grew by nearly 100ft.

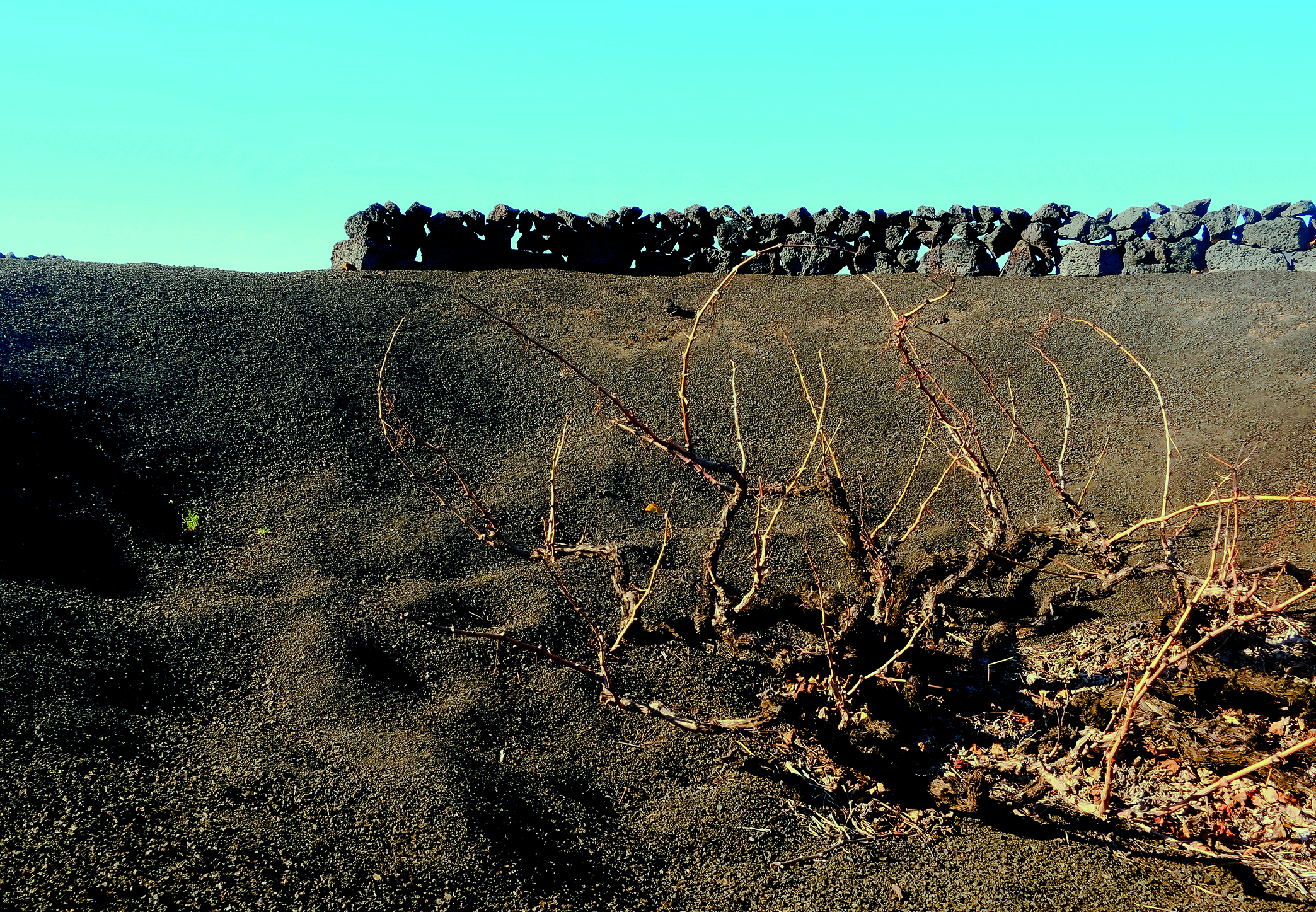

Whatever they have in common, volcanic regions differ vastly — and therefore so do the wines. Climate, grape variety, altitude and geography all play their part, as, of course, do people. White wine from a steep slope with a river at its foot, made principally from the Garganega grape, is going to taste very different from Malvasia grown in depressions like a giant’s thumbprints on black volcanic ash. The former is Soave, the latter is Lanzarote. There are fantastic wines in both places…but you don’t need to be an expert to tell them apart.

One of the first volcanic wine styles I fell for was Assyrtiko from Santorini. The island is now a tourist haven, as it’s a west-facing crescent, perfect for watching sunsets, but that shape is due to the explosion that sank most of it 3,600 years ago. On this porous rock, thirsty vines must wind deep in search of water, but all that effort is good for the lifespan: some vines are upwards of 200 years old. They are trained into circlets that resemble birds’ nests, to shade the grapes from the Greek sun, which looks weird, but it works — these white wines are entirely distinctive, pure and saline.

Gaïa’s textured Wild Ferment and smoky, vivacious Ammonite are standouts, as is the new range by Paris Sigalas, formerly of Domaine Sigalas, who has founded his own label, Oeno P, with the aim of “taking Assyrtiko to a higher level”. His extraordinary wines are aged in clay amphorae, and have notes of white stone fruit and honeysuckle, underlaid with a thrilling minerality. Sigalas has even called one Akulumbo, the local name for the sunken volcano, which is still active.

On Tinos, an island farther north towards the mainland, T-Oinos is making precise Assyrtikos with beautiful acidity on a plateau at 1,500ft that resembles the moon. Mount Teide in Tenerife also looks like a lunar landscape. This is another active volcano: it last erupted in 1909. The Canary Islands’ location off the African coast made them a useful refuelling point for explorers including Christopher Columbus, which meant that, 500 years ago, “Canary wines” were famous around the world, and judging from today’s versions, they deserved to be. Jonatan García Lima of Suertes del Marqués points out that the first wine ever drunk in Australia came from here: Captain Cook was another explorer who stopped by.

García Lima’s vines are huge, thick curling trunks on slopes so steep they can cause vertigo. They produce a red mostly from the indigenous Listán Negro variety, shimmering with cherries and raspberries, while his Listán Blanco Edicíon 1 perfectly balances floral notes with green-apple acidity. Roberto Santana of Envinate is another great Tenerife producer, making exceptionally elegant, flinty wines from, among others, a seaside vineyard called Táganan, where the vines are around 100 years old. And there are even more otherworldly vineyards planted on Lanzarote, in a top layer of black volcanic ash that is the result of a massive volcanic eruption in 1730. At El Grifo (founded in 1775) or Los Bermejos, individual vines sit in small depressions shielded from wind by walls of volcanic rock. The vineyards look like they should produce nothing… but the dry Malvasias, in particular, are delicious.

Italy is dotted with volcanic vineyards, from Soave in the north, near the lovely city of Verona, to Sicily, where the vines grow in the shadow of Mount Etna, belching smoke — and more — above. Soave’s problem is that many of the wines are lacklustre, which hurts the reputation of the top producers: try Pieropan’s La Rocca Soave Classico, an extraordinary, stony single-vineyard Garganega, its citrus acidity softened by hints of honey. Or Gini La Froscà Soave Classico, all smoke, spice and toasted almonds. Like Soave, Sicily, located 670 miles south, has a winemaking history stretching back thousands of years, but the vineyards on Mount Etna were moribund by the 1990s. “Etna was [gloomy] because it was an abandoned volcano,” said the late Andrea Franchetti, who arrived in 2000. “There was the misery of blackened streets and ashen churches… It seemed crazy to restore vineyards so high up the mountain — above, it was erupting — but I liked that they were planted so high.”

Franchetti’s winery, Passopisciaro, is one of the region’s stars, and his six Contrada wines are expressions of the mountain’s Nerello Mascalese grape, all from vines over 70 years old and subtly different, although they all offer combinations of red fruit, rhubarb and black pepper. Planeta, one of Sicily’s most successful wine-producing families, makes several they call Eruzione 1614 because the vines grow on the remains of lava from that year’s big eruption. No surprise perhaps that the local Nerello Mascalese and Carricante varieties like these parched and mineral soils, but so does Riesling, and theirs is electric, with notes of petrol, honeysuckle, lemon and stone.

Hungary’s volcanoes may have been extinct for about two million years, but you can still taste them. Furmint and Hárslevelű, the grapes of the famous sweet Tokaj wines, also produce vibrant dry whites: try Tokaj Nobilis’s single- vineyard Hárslevelű, which has lovely, pure notes of lime and white flower, or Orosz Gábor’s spicy Király Hárslevelű. One of my absolute favourite wines of 2024 was an oddity from this region, Szamarodni Pajzos Tokaj 2011, a tangy dry Muscat that makes a great aperitif.

West of Budapest is Lake Balaton, Central Europe’s largest lake, with stunning landscape to the north, the traditional wine-growing area. Here, strangely flat-topped hills glint blue beyond the vineyards, a lasting reminder of five million years of volcanic activity. This is white wine country, and all sorts of fabulously named grape varieties thrive: perfumed, flinty Kéknyelű, rounded Olaszrizling, tropical and salty, and floral Pinot Gris — known here, catchily, as Szürkebarát.

Sabar’s herbaceous, saline Kéknyelű is a good starting point. Then venture farther north, across the flat plain that was once a sea, to Somló, a small hill thrown up by an ancient underwater volcano, where producers such as Fekete and Kolonics make wine from another intriguing white variety, complex, nutty Juhfark, in Hungary’s smallest wine region.

Our last volcanic outcrop (and another pitstop for busy Christopher Columbus) is the beautiful island of Madeira, off the west coast of Africa, where scenic, walkable streams called levadas lace the richly wooded terrain that gave the place its name. (Madeira in Portuguese means wood.) The wines, which range from dry to sweet, have been famous for centuries: Shakespeare mentions them and wealthy colonial-era Americans were mad for them. To roll their evolution across your tongue, taste Blandy’s, one of the oldest producers, and Barbeito, a mould-breaking whippersnapper. You’ll be astonished by the combination of caramel, hazelnut and orange-peel acidity. But perhaps you shouldn’t be. Those ancient eruptions moved mountains. No wonder they can still move us.